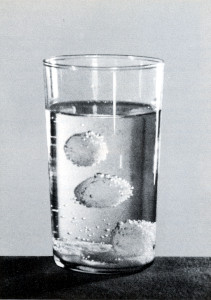

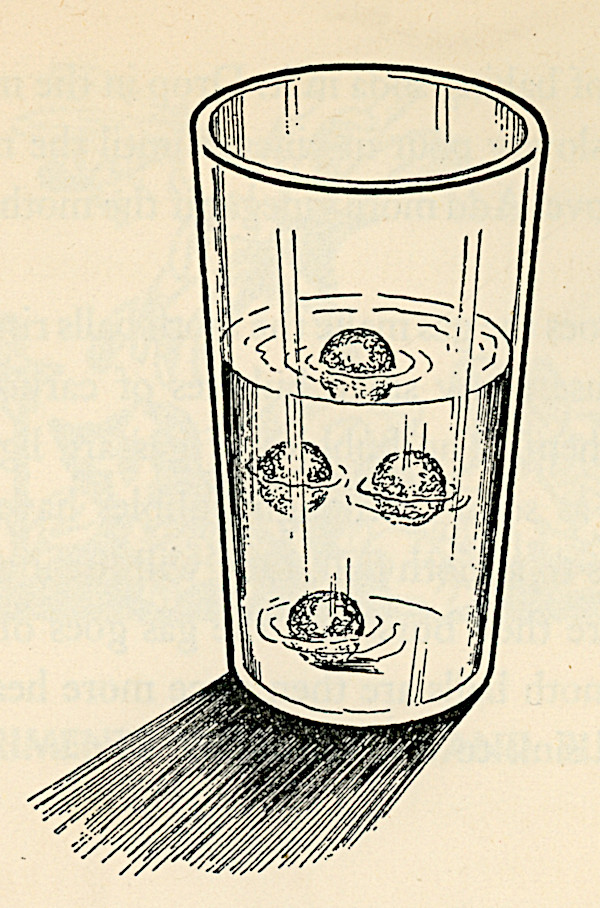

The dancing mothballs demonstration has been performed as a parlor trick at least since the 1940s and probably earlier. Carbon dioxide bubbles from plain soda water or a mixture of water, baking soda and an acid form in the little pits on the surface of a mothball. When enough bubbles accumulate to lift the weight of the mothball, it rises to the surface. There, some of the bubbles of air escape into the atmosphere, and the mothball/raisin, which is denser than the water or soda, sinks, sometimes not all the way to the bottom, to start the cycle over again. Several mothballs in a glass provide the "dancing" effect. The video below gives some idea what they look like; sometimes the dance is livelier.

Before rushing out to buy mothballs, note that this works just as well, if not better, with raisins. Mothballs are made with either naphthalene or 1,4-Dichlorobenzene, both of which are smelly and not without health risks. It is recommended that you should, if you try this at home, use good old fashioned, relatively harmless raisins.

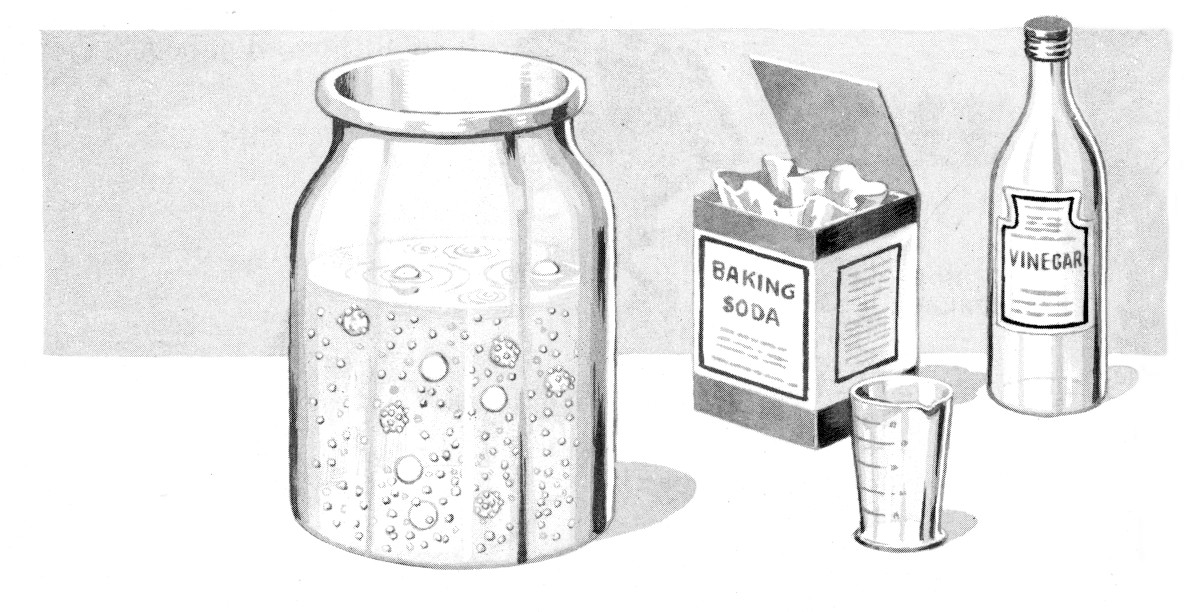

The basic setup is simple. Mostly fill a glass jar with water. Add 1 to 2 teaspoons of baking soda (5 to 10 ml) of baking soda and mix. The trick is to add just enough so it all dissolves and leaves the water clear. Add a few mothballs or, preferably, raisins. Pour in a little vinegar (1/4 cup, 50 ml or so) and the mothballs or raisins should begin to bounce up and down. This also works well with plain soda water.

Sometimes the mothballs / raisins will move a lot, sometimes they will just hang around on the bottom or at the surface. After the jar sits for a few minutes you may see more regular movement. Trial and error will show how much baking soda and vinegar should be used.

The earliest mention of dancing mothballs I've found is in the August 1942 issue of Popular Science though there are likely earlier articles. "How to Put on a Chemical Show" describes it as "an exhibit which you can stand at one end of your magic table, to mystify the spectators throughout the show. Without apparent cause, these balls repeatedly rise to the top of a liquid in a jar, hesitate there a moment, and drop to the bottom again". The procedure is essentially the same. Baking soda is added to a glass of water, mothballs dropped in, then, instead of vinegar, a little tartaric acid is added without stirring.

"Kitchen Chemistry", LIFE, October 4, 1943 recommended adding mothballs to a mixture of vinegar and baking soda in a glass of water. The article assured the reader that "the moth balls will bounce vigorously for hours". A similar article appeared in the February 1944 issue of Popular Mechanics.

Dancing mothballs appear in a children's science book by 1944. Mae and Ira Freeman's Fun with Chemistry titles the project "the soda water gas" but the instructions are the same - water, vinegar and baking soda. "The clinging bubbles act like little life preservers and make the moth balls rise to the top."

Nelson F. Beeler and Franklyn M. Branley cover the topic thoroughly in their 1950 More Experiments in Science, calling it "dancing mothballs". Their version uses soda water added to water, or water, baking soda and vinegar, and they recommend adding more vinegar if the mothballs fail to rise, or after a long while when the action subsides. They also suggest adding a drop of food coloring to make an interesting centerpiece.

It was in at least one primary school textbook in the 1950s, Discovering Why, printed by The John C. Winston Company in 1951. "This dance of mothballs will go on for several hours."

Joseph Leeming calls it a "gas-propelled 'perpetual motion' machine" in his 1954 The Real Book of Science Experiments, giving a similar description to Beeler and Branley's.

Though they were around earlier, dancing raisins seem to have only caught on in the 1980s, coincidentally around the same time as another famous group of dancing raisins.

Along with raisins, there are quite a few other small objects that will "dance" in carbonated water. The old Bizarre Labs even received a letter about a couscous grain in seltzer water. The key is that whatever objects are used must be able to trap air bubbles on their surface, they need to be light enough to be buoyed to the surface by the bubbles, and they have to be something that won't dissolve in the liquid.

If you happen to be drinking champagne or a sparkling wine, raisins will bounce in the glass for a very long time.

Thomas Castagno writes to add that "if you pour (your favorite clear lemon-lime soda) into a clear glass cup, add some salt to the soda and put some Jell-O into the cup that after a while the Jell-O will bounce up and down inside of the cup as air bubbles accumulate and come off of the Jell-O." I haven't personally attempted this yet, but I'm imagining small bits of (lime green?) Jell-O are used.

Swezey, Kenneth M. "How to Put On a Chemical Show". Popular Science August 1942, p. 190

"Kitchen Chemistry", LIFE, October 4, 1943, p. 125

"Chemical Magic". Popular Mechanics, February 1944, p. 46

Freeman, Mae and Ira. Fun with Chemistry. New York: Random House, 1944.

Beeler, Nelson F. and Franklyn M. Branley. More Experiments in Science. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1950.

Dowling, Thomas I., Kenneth Freeman, Nan Lacy and James S. Tippett. Discovering Why. Toronto: The John C. Winston Company, 1952 (U.S. edition 1951).

Carlson, Bernice Wells. Do It Yourself! New York: Abingdon Press, 1952.

Leeming, Joseph. The Real Book of Science Experiments.Garden City, NY: Garden City Books, 1954.

Dowling, Bizarre Labs (video), Freeman, Leeming, Bizarre Labs (video)

This article was printed from the Bizarre Labs website at bizarrelabs.com